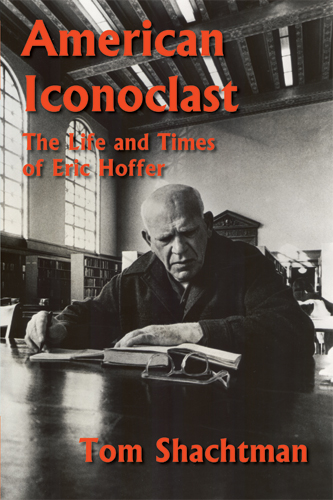

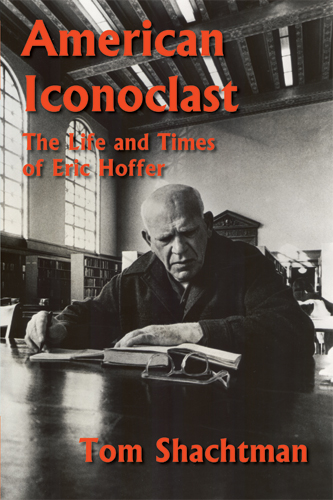

photo by Mark Connolly

Listen to the Shachtman interview

American Iconoclast: The Life and Times of Eric Hoffer

by Tom Shachtman

available from

Hopewell Publications

and all bookstores

|

photo by Mark Connolly Listen to the Shachtman interview

|

American Iconoclast: The Life and Times of Eric Hoffer available from |

|

“Excellent new biography…. [Hoffer's] name has gradually faded from view. Yet, as his biographer points out, Hoffer continues to contribute insightful ideas and opinions to society, which is why we ought to look to his writings once again.” |

Excerpt from American Iconoclast: The Life and Times of Eric Hoffer by Tom Shachtman Late May of 1967 was a time of restlessness and social upheaval in the United States of America. The war in Vietnam, involving a half-million American troops, was at its height and in danger of being lost. Some Americans were chagrined at that possibility while others were not at all dismayed. Headlines in San Francisco’s newspapers reported protests at the Berkeley campus of the University of California against continued American involvement in that war, and Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. had come out in favor of an American withdrawal. Inflation had begun to take its toll on the economy. There were occasional riots in the ghettoes of large cities, partly in reaction to African-American rage at chronic unemployment, partly at the slow pace of civil rights progress. In San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, the “summer of love” had begun, an anarchic cultural gathering of youth in rebellion whose rejection of traditional values was stoking the fires of an intergenerational clash. A shooting war loomed in the Middle East and would likely draw the U.S. into it on the side of Israel and bring in the Soviet Union on the side of some Arab countries. Soviet aircraft tested American and British airspace while Red China threatened the integrity of America’s ally, Taiwan. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s popularity was declining so rapidly as to raise the question of whether he could be re-elected in 1968. Increasing polarization between blacks and whites, hawks and doves, haves and have-nots seemed to be leaching away American civilization and democracy. It was also an era in which Americans turned increasingly to newspapers, magazines, and especially to television to keep track of and attempt to understand the seismic changes going on around them. For several months, emissaries from the leading network news organization, CBS News, had been shuttling from the East Coast to San Francisco to entreat Eric Hoffer, the aging dockworker, former agricultural migrant, Berkeley lecturer, and author of books on mass movements and drastic change, to grant a long interview to the network’s chief commentator, Eric Sevareid. Hoffer, known as an astute social observer, was suddenly hot: in January he had been profiled in The New Yorker, and in March was the subject of a Life photo-essay, “Docker of Philosophy,” articles themselves stimulated by a series of public television conversations with Hoffer conducted by James Day of KQED. Perhaps a quarter-million people had seen Hoffer on the then-new public television network; a CBS prime-time interview could expose him to an audience a hundred times that size, 25 million people. The major networks’ half-hour early evening newscasts had surpassed the daily newspapers as Americans’ main source of information. Polls regularly chose CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite as “the most trusted man in America,” and ranked Sevareid not far behind. Many writers might have jumped at the opportunity to voice their opinions to 25 million people, but CBS had not found it easy to secure Hoffer’s agreement. The “longshoreman philosopher,” as his publisher had christened him, still worked on the docks and adhered to an ascetic lifestyle, residing alone in a small, Spartan walk-up in a rooming-house atop one of Chinatown’s steep hills, with no car, no telephone, and no television. Sometimes he did not even respond to telegrams delivered to his door. Sevareid wanted to interview Hoffer because of his keen understandings of human behavior: Hoffer’s insight that the ranks of Nazism and Communism were filled by similar “true believers” although they espoused opposite ideologies had become the way many Americans now understood America’s World War II and Cold War enemies. President Dwight Eisenhower had touted Hoffer’s first and most successful book, The True Believer, as had philosopher Bertrand Russell. “Blind faith is to a considerable extent a substitute for the lost faith in ourselves; insatiable desire a substitute for hope; accumulation a substitute for growth; fervent hustling a substitute for purposeful action; and pride a substitute for unattainable self-respect,” Hoffer had written in his second big book, The Ordeal of Change. In recent years, with clarity and wit Hoffer had gone beyond analysis of mass movements to dissect the roles of intellectuals and misfits in various historical eras, the fault-line in individuals’ minds that gave rise both to creativity and to blind obedience, the relation-ship between human progress and nature, and other grand subjects, as well as addressing current issues such as student anti-war protests and civil rights aspirations. But although a half-million copies of his books had been sold, the vast majority of America’s 200 million people still were not aware of Eric Hoffer. ... |

website copyright © Hopewell Publications |